Lalitha was born on 27th August 1919 in a middle class Telegu family in Chennai. She was the fifth of seven children. Her father and all of her brothers were engineers from College of Engineering, Guindy (CEG), University of Madras, while her sisters were educated up to 10th grade. While it is still a concern, the practice of early marriage was common during those times. Lalitha was married at the age of 15. Her parents insisted that she continue her education even after marriage. Although it came to a stop after she completed her Secondary School or 10th grade education. In 1937, at the age of 18 she gave birth to her daughter Syamala. Just four months later, her husband passed away.

Being a young mother is difficult, being a widow with a baby, even more so. Widows in India face a lot of challenges, often based in tradition. Some such traditions have been extremely inhumane. From Sati, which forced women into a ritualistic immolation on husband’s pyre to having to renounce all wealth and their identity. In most parts of India women are still forced or socially pressured into giving up vanity, sometimes including only wearing white sarees and shaving their heads, and be excluded from all social events. These issues and other factors force women to live out their lives in Ashrams especially made for them. At Society of Women Engineers’ first international conference in 1964, Lalitha said “150 years ago, I would have been burned at the funeral pyre with my husband’s body “. Her daughter Syamala said (to The Better India), “When my father passed away, mom had to suffer more than she should have. Her mother-in-law had lost her 16th child and took out that frustration on the young widow. It was a coping mechanism and today, I understand what she was going through. However, my mother decided not to succumb to societal pressures. She would educate herself and earn a respectable job.”

Lalitha wanted to become self-sufficient and support her daughter, so she decided to get a professional degree. She joined Queen Mary’s College in Chennai and completed her Intermediate education with first class. Women in India had started earning regular degrees by now. Some of the most famous pioneers being Janaki Ammal and Kadambini Ganguly. Most of these were in Medical field but a career in medicine did not seem appealing to Lalitha as she did not want to leave baby Syamala during field work. Instead, she wanted to become an engineer like her father and brothers. She wanted a regular-hours job so she could spend time with and raise her daughter. Her father, Pappu Subba Rao was a teacher at CEG, he approached the principal Dr. K.C. Chacko on her behalf. While her grades were good enough for a man to get into CEG, they had to not only convince the Principal but also take permission from the British government. The Principal and Director of Public Instruction RM Statham, decided it was time for the college to admit Women Students.

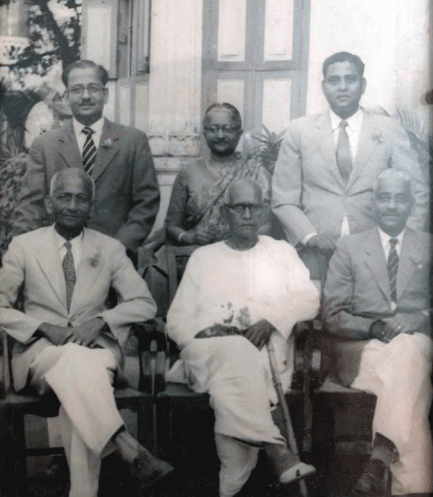

Lalitha was granted an admission in 1940 into the four-year electrical engineering program. After the initial reluctance, authorities and officials of the college were supportive of her. Syamala says, “Contrary to what people might think, the students at amma’s college were extremely supportive. She was the only girl in a college with hundreds of boys but no one ever made her feel uncomfortable and we need to give credit to this. The authorities arranged for a separate hostel for her too. I used to live with my uncle while amma was completing college and she would visit me every weekend”. After a few months, at the initiative of Lalitha’s father, CEG advertised open admissions for women. As a result, two more women entered the college in the same year, Leelamma George and P. K. Theressia, who were remarkable in their own right.

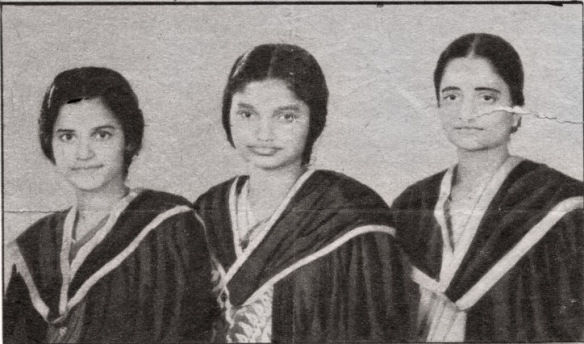

Lalitha, Thressia, and Leelamma graduated from CEG in 1943. Syamala explains, “Both of them were juniors to my mother by a year. However, all three of them graduated together because the second world war was at its peak in 1944 and the university decided to cut down the engineering course by a few months”. Thressia and Leelamma got their regular degree in Civil Engineering. Thressia went on to be the first woman Chief Engineer for PWD. Lalitha stayed for another year and got her Honors Degree in Electrical Engineering in 1944. All of their certificates had handwritten ‘She’ in place of ‘He’.

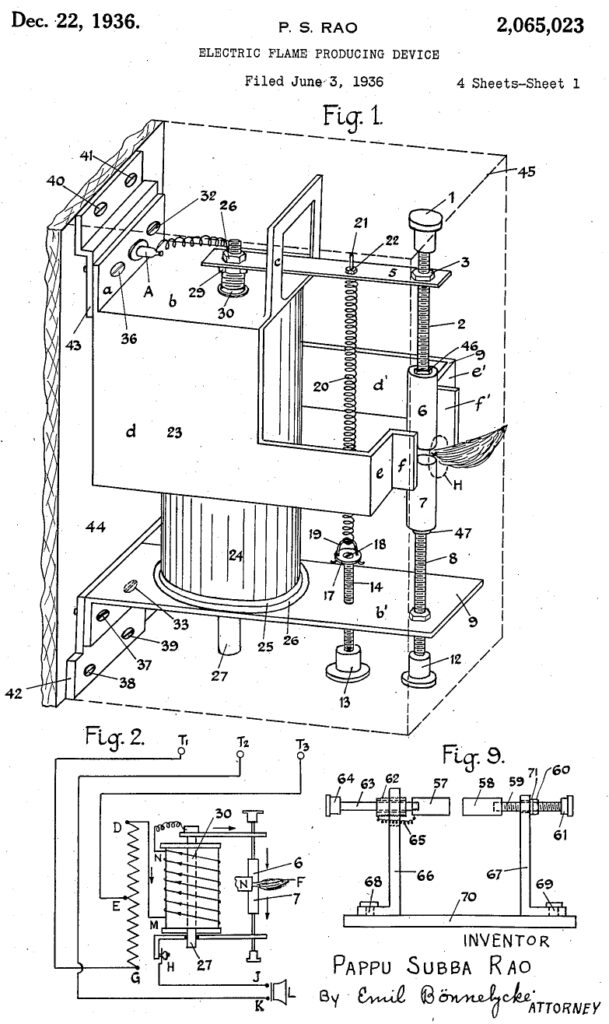

Lalitha started an apprenticeship at Jamalpur Railway Workshop in 1943 to complete practical training for her degree. After one year at Jamalpur, she joined the Central Standards Organization of India as an Engineering Assistant. Her job was in Shimla which made it possible for her to work and live with her Brother’s family. Her sister in law helped her raise the then six-year-old Syamala. She stayed at this job for a couple of years till 1946, after which at her father’s request she left to support him in his research. Her father filed a number of patents during this time, presumably with her help. A few of them being Jelectromonium, which was an electrical musical instrument, a smokeless oven, and an electric flame producer. While she enjoyed it, she could not continue it because of financial issues. In 1948, she joined Associated Electrical Industries, a British firm. She decided to apply for this job also because this was in Kolkata, she could live with her second brother which would help with raising Syamala. Additionally, being a single mother and a widow, it would have been difficult for her to find a place to live.

Syamala says, “My aunt lived in Kolkata and had a son about my age. We were very close and so, amma used to go to work leaving me with my cousin and aunt. That’s how I grew up. Although, today, I can understand how important my mother is in the history of women’s education in India as well as in the history of engineering, back then, all I knew was that my mom is an engineer—just another engineer”. She also recalls her grandparent’s role in her upbringing during this time, “While my mom was in AEI, I was in school in Chennai living with my maternal grandparents. They played a big role in my life as long as I lived with them. My grandfather encouraged me in sports and came to watch my athletic competitions representing my school. He also incorporated politics into my life. When I came to live with my mom in Calcutta and joined Loreto College, he would come watch me playing basketball and tennis. My grandmother also had a political streak and so now I am very open about my political bent of mind”.

She had a very long and stable career at AEI. She worked in the engineering department and the sales division. Over the years she worked at multiple projects most notably she worked on the electrical generators for the Bhakra Nangal Dam, one of the largest dams in India. She also worked on transmission lines design and later on in execution of contracts. Syamala’s husband and Lalitha’s son-in-law who is also an electrical engineer explains, “Gradually the designing part was discarded and the activity focused on contract engineering, serving as an intermediary between the equipment manufacturers in England and the local installation and servicing engineers. She continued to work in the same office of AEI, which in later years was taken over by the General Electric Company (GEC) and retired after over thirty odd years.”

At the 1964 First International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists

Council of the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE), London, appointed her an associate member in 1953, she later became a full member. Another highlight of her career would be invitation to the First International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists (ICWES) in New York. She represented India at the conference in June 1964 in a private capacity as there was no Indian Chapter then. The goal of the conference was to increase the participation of women in STEM. Talking about this conference, Lalitha said “The conference resolved to encourage women to increase their participation in the professional societies in their countries and improve their qualifications not only during their student days but throughout their professional life. It also resolved to maintain the central file of Women Engineers and Scientists used for this conference and enlarge it as much as possible”. On the way back she toured AEI factories in the UK.

After coming back from the conference Lalitha started working for the cause of women in engineering. She gave a number of interviews in magazines and newspapers about the importance of allowing women to participate in the field. She encouraged more Indian women engineers to attend the Second International Conference for Women Engineers & Scientists, held in Cambridge in 1967. As a direct result, five women engineers were able to attend the event. Lalitha retired in 1977 and started traveling with her sister. At the age of 60, she had a brain aneurysm and after a few weeks, she passed away.

Syamala says, she never felt the absence of her father because of the strong support she received from her mother. “I had the most open-minded mother of those times. She never stopped me from doing what I wanted, but at the same time kept me on track. She encouraged me to teach early and made me go on to completing my BEd after marriage”.

Lalitha believed that widows should remarry, although she herself never did. Syamala adds, “She never remarried and never made me feel the absence of a father in my life. She believed that people come into your life for a reason and leave when the purpose is over. I never asked her why she never got married again. But when my husband asked her, she had replied, “To take care of an old man again? No, thank you!”

Syamala studied Science and Education and was a teacher for over 30 years in India. Her husband is a retired scientist and so are her children. In 1994 she moved to the US and continues to teach mathematics to her students in her 80s. This shows how allowing one-person education can have exponential results over generations. Lalitha’s achievements are incredible, they could not have been possible without the extensive support structure that she had. A common theme among all the stories we have explored so far is supportive parents. In Lalitha’s case, her father not only encouraged her but also put his efforts behind other women who wanted to study. Lalitha’s siblings and in-laws all raised Syamala as their own. Lalitha lived with her brother and sister in law for 35 years, as a family, supporting each other.

A single candle is enough to defy the darkness, but a bunch of them are enough to bring about a revolution.

I would like to specially thank Ms. Syamala Chenulu, who took the time out to help me with a lot of information, context, and filled in some gaps in the story of her mother.

As you might have noticed, this article was slightly shorter than our regular ones. We have decided on some changes and want to give you all an update. Since this is a new project and we are getting unexpectedly good response we will continue to experiment and try to improve this. In coming days, we will be putting out one episode per two weeks as compared to a weekly episode right now. This additional time would allow us to produce better content with better research. This would also allow us to expand and get more voices on this platform. There are new things coming and we are excited to share them with you. Thank you for sticking with us, and I would also like to thank all my collaborators who have helped me so far.

Sources:

- https://mathisarovar.com/2017/05/20/love-of-electrical-engineering-was-in-her-blood-lalitha-rao-the-first-indian-woman-engineer/

- https://www.thebetterindia.com/185532/india-first-woman-engineer-a-lalitha-inspiring-history/

- https://www.thehindu.com/society/indias-first-woman-electrical-engineer/article19102674.ece

- https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/5b/66/69/219ebaeb4ef08e/US2065023.pdf